R Programming Basics

This guide introduces the fundamentals of R programming, focusing on data manipulation with the tidyverse, particularly dplyr. These basics are essential before diving into OMOP-specific analyses.

Who is this guide for?

This guide is written for anyone who wants to work with databases in a “tidyverse” style—a human-centered, consistent, and composable approach to data analysis.

- New to R? We recommend complementing this guide with R for Data Science.

- New to databases? Familiarize yourself with SQL basics through tutorials like SQLBolt or SQLZoo.

- New to the OMOP CDM? This guide is best paired with The Book of OHDSI.

Bridging the Gap for Different Backgrounds

This guide is designed to be accessible to readers from various backgrounds. Here’s how we address common challenges:

For SAS Programmers

If you’re coming from SAS, you might find the functional programming style of R unfamiliar. Here’s a quick mapping of common SAS concepts to their R/dplyr equivalents:

| SAS Concept | R/dplyr Equivalent | Description |

|---|---|---|

PROC SQL | dplyr verbs like filter(), select(), mutate() | Querying and manipulating data |

DATA step | mutate() or transmute() | Creating or modifying variables |

PROC SORT | arrange() | Sorting data |

PROC SUMMARY | group_by() + summarise() | Grouping and aggregating data |

PROC FREQ | count() | Frequency tables |

Remember, in R, operations are chained using the pipe (|>) for readability, similar to how you might chain procedures in SAS.

For Clinical Experts

If you’re new to data analysis but have a strong clinical background, the OMOP CDM might seem overly complex at first. Think of it as a standardized “language” for health data:

- Why separate tables? Instead of one big spreadsheet, data is split into logical tables (e.g.,

personfor demographics,condition_occurrencefor diagnoses) to avoid repetition and ensure consistency. - What are concept IDs? These are standardized codes for medical terms (e.g., “Type 2 Diabetes” might have ID 201826). They ensure everyone uses the same definitions, making research comparable.

- Why vocabularies? OMOP uses controlled vocabularies (like SNOMED or ICD) to map local codes to standard ones, reducing ambiguity.

This structure allows for powerful, scalable analyses across different healthcare systems.

For Data Scientists New to Healthcare (like Martina)

If you’re proficient in R but unfamiliar with clinical research, we’ll explain the “why” behind the code. For example, when we create a “cohort” of patients, it’s not just filtering data—it’s defining a study population based on clinical criteria to answer specific research questions.

How is this guide organized?

This guide is divided into two main parts:

- General Principles for Working with Databases in R: The first half focuses on the foundational concepts of using tidyverse-style code to build analytical pipelines. You will learn how to connect to a database, manipulate data, and prepare it for analysis without ever leaving the R environment.

- Applying these Principles to the OMOP CDM: The second half demonstrates how to apply these general principles specifically to the OMOP Common Data Model. We will explore a suite of specialized R packages that streamline common analytical tasks in observational health research.

Detailed Chapters Overview

For a deeper dive, the underlying technical manual for this guide is structured into the following detailed chapters. While this page provides a high-level summary, the full manual offers comprehensive examples and technical explanations.

1. A first analysis using data in a database

The iris dataset is a classic example in data science, collected by Edgar Anderson in 1935. It contains measurements of 150 iris flowers from three species: setosa, versicolor, and virginica. Each flower has four measurements: sepal length, sepal width, petal length, and petal width (all in centimeters). The goal is often to classify the species based on these measurements, making it a simple but effective dataset for demonstrating statistical and machine learning techniques.

Setting Up Your Environment

First, you need to install and load the necessary R packages.

# Load the libraries

library(dplyr)

library(dbplyr)

library(ggplot2)

library(DBI)

library(duckdb)

Inserting Data into a Database

Next, we will load the iris data into an in-memory duckdb database. This simulates a real-world scenario where your data resides in a database server.

# Create an in-memory duckdb database

db <- dbConnect(drv = duckdb())

# Write the iris dataframe to a table named "iris" in the database

dbWriteTable(db, "iris", iris)

# You can see the tables in the database

dbListTables(db)

## [1] "iris"

# > [1] "iris"

From R to SQL: The Power of dbplyr

Now that the data is in a database, we could query it using SQL. However, the magic of the dbplyr package is that it allows you to write familiar dplyr code, which it automatically translates into SQL for you.

First, create a reference to the iris table in the database.

iris_db <- tbl(db, "iris")

Now, you can use standard dplyr verbs on this object.

# Get a summary of sepal length by species

iris_db |>

group_by(Species) |>

summarise(

n = n(),

mean_sepal_length = mean(Sepal.Length, na.rm = TRUE)

)

## # Source: SQL [?? x 3]

## # Database: DuckDB 1.4.0 [gabriel.maeztu@Darwin 25.0.0:R 4.5.1/:memory:]

## Species n mean_sepal_length

## <fct> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 setosa 50 5.01

## 2 versicolor 50 5.94

## 3 virginica 50 6.59

When you run this code, dbplyr translates it into the following SQL query, sends it to the database, and returns the result.

<SQL>

SELECT

"Species",

COUNT(*) AS n,

AVG("Sepal.Length") AS mean_sepal_length

FROM iris

GROUP BY "Species"

Bringing Data into R for Visualization

While most data manipulation should happen in the database for efficiency, you will often need to bring the final, summarized data back into R for visualization or modeling. The collect() function does this.

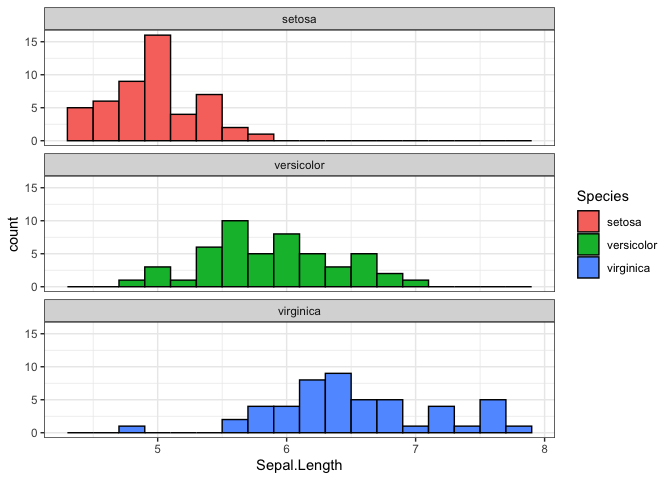

Let’s create a histogram of sepal length for each flower species.

iris_db |>

select("Species", "Sepal.Length") |>

collect() |> # This brings the data from the database into an R dataframe

ggplot(aes(x = `Sepal.Length`, fill = Species)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 0.2, colour = "black") +

facet_wrap(~Species, ncol = 1) +

theme_bw()

This workflow—manipulating data in the database and collecting only the results—is the most efficient way to work with large datasets.

Disconnecting from the Database

When you are finished with your analysis, it is good practice to close the connection to the database.

dbDisconnect(db)

2. Core verbs for analytic pipelines utilising a database

To demonstrate working with multiple tables, we’ll extend the iris example by creating related tables. We’ll split the data into separate tables for species information and measurements, then show how to join them back together.

Setting Up the Database with Multiple Tables

# Create database

db <- dbConnect(duckdb())

# Split iris into two tables: species info and measurements

species_info <- iris |> select(Species) |> distinct() |> mutate(species_id = row_number())

measurements <- iris |> left_join(species_info, by = "Species")

# Write tables

dbWriteTable(db, "species_info", species_info)

dbWriteTable(db, "measurements", measurements)

# Create lazy references

species_db <- tbl(db, "species_info")

measurements_db <- tbl(db, "measurements")

Selecting Rows: filter() and distinct()

Use filter() to select rows based on conditions. For example, to find measurements with sepal length > 5:

measurements_db |>

filter(Sepal.Length > 5) |>

select(Species, Sepal.Length)

## # Source: SQL [?? x 2]

## # Database: DuckDB 1.4.0 [gabriel.maeztu@Darwin 25.0.0:R 4.5.1/:memory:]

## Species Sepal.Length

## <fct> <dbl>

## 1 setosa 5.1

## 2 setosa 5.4

## 3 setosa 5.4

## 4 setosa 5.8

## 5 setosa 5.7

## 6 setosa 5.4

## 7 setosa 5.1

## 8 setosa 5.7

## 9 setosa 5.1

## 10 setosa 5.4

## # ℹ more rows

distinct() removes duplicate rows:

measurements_db |>

distinct(Species)

## # Source: SQL [?? x 1]

## # Database: DuckDB 1.4.0 [gabriel.maeztu@Darwin 25.0.0:R 4.5.1/:memory:]

## Species

## <fct>

## 1 setosa

## 2 virginica

## 3 versicolor

Ordering Rows: arrange()

arrange() sorts rows by one or more columns:

measurements_db |>

arrange(desc(Sepal.Length)) |>

select(Species, Sepal.Length)

## # Source: SQL [?? x 2]

## # Database: DuckDB 1.4.0 [gabriel.maeztu@Darwin 25.0.0:R 4.5.1/:memory:]

## # Ordered by: desc(Sepal.Length)

## Species Sepal.Length

## <fct> <dbl>

## 1 virginica 7.9

## 2 virginica 7.7

## 3 virginica 7.7

## 4 virginica 7.7

## 5 virginica 7.7

## 6 virginica 7.6

## 7 virginica 7.4

## 8 virginica 7.3

## 9 virginica 7.2

## 10 virginica 7.2

## # ℹ more rows

Column Transformation: mutate(), select(), rename()

mutate() creates or modifies columns:

measurements_db |>

mutate(

sepal_ratio = Sepal.Length / Sepal.Width,

is_large = Sepal.Length > 6

) |>

select(Species, sepal_ratio, is_large)

## # Source: SQL [?? x 3]

## # Database: DuckDB 1.4.0 [gabriel.maeztu@Darwin 25.0.0:R 4.5.1/:memory:]

## Species sepal_ratio is_large

## <fct> <dbl> <lgl>

## 1 setosa 1.46 FALSE

## 2 setosa 1.63 FALSE

## 3 setosa 1.47 FALSE

## 4 setosa 1.48 FALSE

## 5 setosa 1.39 FALSE

## 6 setosa 1.38 FALSE

## 7 setosa 1.35 FALSE

## 8 setosa 1.47 FALSE

## 9 setosa 1.52 FALSE

## 10 setosa 1.58 FALSE

## # ℹ more rows

select() chooses specific columns:

measurements_db |>

select(Species, Sepal.Length, Petal.Length)

## # Source: SQL [?? x 3]

## # Database: DuckDB 1.4.0 [gabriel.maeztu@Darwin 25.0.0:R 4.5.1/:memory:]

## Species Sepal.Length Petal.Length

## <fct> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 setosa 5.1 1.4

## 2 setosa 4.9 1.4

## 3 setosa 4.7 1.3

## 4 setosa 4.6 1.5

## 5 setosa 5 1.4

## 6 setosa 5.4 1.7

## 7 setosa 4.6 1.4

## 8 setosa 5 1.5

## 9 setosa 4.4 1.4

## 10 setosa 4.9 1.5

## # ℹ more rows

rename() changes column names:

measurements_db |>

rename(sepal_length = Sepal.Length)

## # Source: SQL [?? x 6]

## # Database: DuckDB 1.4.0 [gabriel.maeztu@Darwin 25.0.0:R 4.5.1/:memory:]

## sepal_length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species species_id

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <fct> <int>

## 1 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 setosa 1

## 2 4.9 3 1.4 0.2 setosa 1

## 3 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 setosa 1

## 4 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 setosa 1

## 5 5 3.6 1.4 0.2 setosa 1

## 6 5.4 3.9 1.7 0.4 setosa 1

## 7 4.6 3.4 1.4 0.3 setosa 1

## 8 5 3.4 1.5 0.2 setosa 1

## 9 4.4 2.9 1.4 0.2 setosa 1

## 10 4.9 3.1 1.5 0.1 setosa 1

## # ℹ more rows

Grouping and Aggregation: group_by(), summarise(), count()

group_by() groups data for calculations:

measurements_db |>

group_by(Species) |>

summarise(

avg_sepal = mean(Sepal.Length, na.rm = TRUE),

count = n()

)

## # Source: SQL [?? x 3]

## # Database: DuckDB 1.4.0 [gabriel.maeztu@Darwin 25.0.0:R 4.5.1/:memory:]

## Species avg_sepal count

## <fct> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 setosa 5.01 50

## 2 versicolor 5.94 50

## 3 virginica 6.59 50

count() is a shortcut for counting:

measurements_db |>

count(Species, sort = TRUE)

## # Source: SQL [?? x 2]

## # Database: DuckDB 1.4.0 [gabriel.maeztu@Darwin 25.0.0:R 4.5.1/:memory:]

## # Ordered by: desc(n)

## Species n

## <fct> <dbl>

## 1 setosa 50

## 2 versicolor 50

## 3 virginica 50

Joining Tables

Joins combine data from multiple tables. For example, to join measurements with species info:

measurements_db |>

left_join(species_db, by = "Species") |>

select(Species, Sepal.Length)

## # Source: SQL [?? x 2]

## # Database: DuckDB 1.4.0 [gabriel.maeztu@Darwin 25.0.0:R 4.5.1/:memory:]

## Species Sepal.Length

## <fct> <dbl>

## 1 setosa 5.1

## 2 setosa 4.9

## 3 setosa 4.7

## 4 setosa 4.6

## 5 setosa 5

## 6 setosa 5.4

## 7 setosa 4.6

## 8 setosa 5

## 9 setosa 4.4

## 10 setosa 4.9

## # ℹ more rows

Constructing a Tidy Analytic Dataset

Let’s create a comprehensive dataset by joining tables and performing aggregations:

analytic_dataset <- measurements_db |>

group_by(Species) |>

summarise(

avg_sepal_length = mean(Sepal.Length, na.rm = TRUE),

avg_petal_length = mean(Petal.Length, na.rm = TRUE),

total_measurements = n()

) |>

arrange(desc(avg_sepal_length))

# Collect results

analytic_dataset |> collect()

## # A tibble: 3 × 4

## Species avg_sepal_length avg_petal_length total_measurements

## <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 virginica 6.59 5.55 50

## 2 versicolor 5.94 4.26 50

## 3 setosa 5.01 1.46 50

This pipeline demonstrates how to build complex queries using dplyr verbs, with all operations pushed to the database for efficiency.

3. Supported expressions for database queries

Data Type Conversions

R and SQL handle data types differently. dbplyr automatically converts many types, but understanding the mappings is important:

- Logical:

TRUE/FALSE→TRUE/FALSEor1/0 - Character: Strings remain strings

- Numeric: Integers and doubles are preserved

- Dates:

Dateobjects →DATE - Datetimes:

POSIXct→TIMESTAMP

Logical Comparisons and Operators

Standard comparison operators work as expected:

measurements_db |> filter(Sepal.Length > 5 & Petal.Length > 3)

## # Source: SQL [?? x 2]

## # Database: DuckDB 1.4.0 [gabriel.maeztu@Darwin 25.0.0:R 4.5.1/:memory:]

## Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species species_id

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <fct> <int>

## 1 7 3.2 4.7 1.4 versicolor 2

## 2 6.4 3.2 4.5 1.5 versicolor 2

## 3 6.9 3.1 4.9 1.5 versicolor 2

## 4 5.5 2.3 4 1.3 versicolor 2

## 5 6.5 2.8 4.6 1.5 versicolor 2

## 6 5.7 2.8 4.5 1.3 versicolor 2

## 7 6.3 3.3 4.7 1.6 versicolor 2

## 8 6.6 2.9 4.6 1.3 versicolor 2

## 9 5.2 2.7 3.9 1.4 versicolor 2

## 10 5.9 3 4.2 1.5 versicolor 2

## # ℹ more rows

# Translates to: WHERE "Sepal.Length" > 5 AND "Petal.Length" > 3

Conditional Statements

if_else() and case_when() are supported:

measurements_db |>

mutate(

size_category = case_when(

Sepal.Length < 5 ~ "small",

Sepal.Length <= 6 ~ "medium",

TRUE ~ "large"

)

)

## # Source: SQL [?? x 7]

## # Database: DuckDB 1.4.0 [gabriel.maeztu@Darwin 25.0.0:R 4.5.1/:memory:]

## Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species species_id

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <fct> <int>

## 1 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 setosa 1

## 2 4.9 3 1.4 0.2 setosa 1

## 3 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 setosa 1

## 4 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 setosa 1

## 5 5 3.6 1.4 0.2 setosa 1

## 6 5.4 3.9 1.7 0.4 setosa 1

## 7 4.6 3.4 1.4 0.3 setosa 1

## 8 5 3.4 1.5 0.2 setosa 1

## 9 4.4 2.9 1.4 0.2 setosa 1

## 10 4.9 3.1 1.5 0.1 setosa 1

## # ℹ more rows

## # ℹ 1 more variable: size_category <chr>

SQL translation:

CASE

WHEN "Sepal.Length" < 5 THEN 'small'

WHEN "Sepal.Length" <= 6 THEN 'medium'

ELSE 'large'

END

String Functions

Common string operations:

species_db |>

mutate(

species_upper = toupper(Species),

species_length = nchar(Species),

species_substr = substr(Species, 1, 3)

)

## # Source: SQL [?? x 5]

## # Database: DuckDB 1.4.0 [gabriel.maeztu@Darwin 25.0.0:R 4.5.1/:memory:]

## Species species_id species_upper species_length species_substr

## <fct> <int> <chr> <dbl> <chr>

## 1 setosa 1 SETOSA 6 set

## 2 versicolor 2 VERSICOLOR 10 ver

## 3 virginica 3 VIRGINICA 9 vir ```

Database-Specific Considerations

While dbplyr aims for portability, some functions may behave differently:

- DuckDB: Full support for most R functions

- PostgreSQL: Excellent date/time support

- SQL Server: May require workarounds for some functions

Always test your queries on your target database system.

4. Building analytic pipelines for a data model

Principles of Modular Pipelines

- Separation of Concerns: Break down complex queries into smaller, focused steps

- Reusability: Create functions for common operations

- Readability: Use clear variable names and comments

- Efficiency: Minimize data movement between database and R

Example: Analyzing Iris Measurements

Building on the iris example, let’s create a pipeline to analyze measurements by species:

# Step 1: Filter and prepare data

iris_performance <- measurements_db |>

filter(!is.na(Sepal.Length), !is.na(Petal.Length))

# Step 2: Calculate metrics

performance_metrics <- iris_performance |>

mutate(

sepal_petal_ratio = Sepal.Length / Petal.Length,

is_large_flower = as.numeric(Sepal.Length > 6)

) |>

group_by(Species) |>

summarise(

total_flowers = n(),

avg_sepal_petal_ratio = mean(sepal_petal_ratio, na.rm = TRUE),

large_percentage = mean(is_large_flower, na.rm = TRUE) * 100

)

# Step 3: Filter for significant groups

significant_species <- performance_metrics |>

filter(total_flowers >= 40) |>

arrange(desc(avg_sepal_petal_ratio))

# Collect results

results <- significant_species |> collect()

Creating Reusable Functions

For repeated operations, create functions:

calculate_ratios <- function(measurements_tbl) {

measurements_tbl |>

mutate(

sepal_petal_ratio = Sepal.Length / Petal.Length,

is_large = as.numeric(Sepal.Length > 6)

) |>

summarise(

total = n(),

avg_ratio = mean(sepal_petal_ratio, na.rm = TRUE),

large_pct = mean(is_large, na.rm = TRUE)

)

}

# Use the function

species_ratios <- measurements_db |>

group_by(Species) |>

calculate_ratios()

Handling Complex Joins in Relational Models

In structured data models like OMOP, you’ll often need to join multiple tables. Plan your joins carefully:

- Identify the central table (e.g.,

personin OMOP) - Determine the join keys

- Consider the join type (left, inner, etc.)

- Chain joins logically

This approach ensures your pipelines are maintainable and efficient.